McClain's:

Can you tell us about an engraving of yours that you consider your favorite?

Barry Moser:

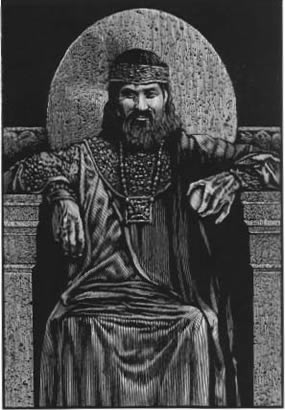

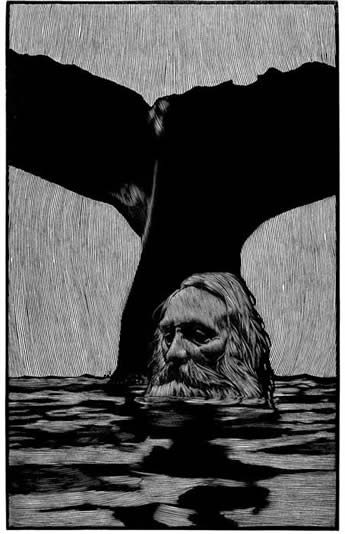

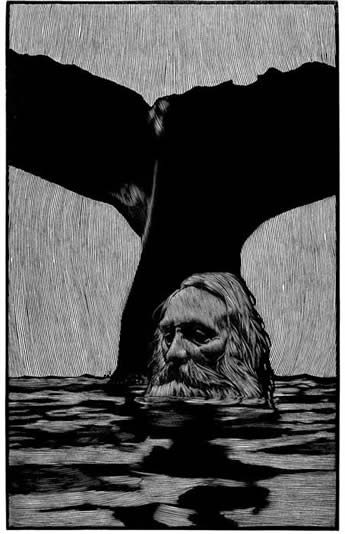

Where to start? With the one that just popped into my head I reckon…”And the Sea Stopped Raging,” in the book of Jonah in the Pennyroyal Caxton Bible. Ask me tomorrow and I’ll give you a different answer.

This image, to recap the above, if it is a good image, is good because of its structure and composition. The large, simple black area contrasted against the complex engraving of the areas around it (note that I am avoiding words that define or refer to subject matter) give it its impact. Its gestalt. That the black area represents the flukes of a whale is, as far as the image goes, irrelevant. However, as far as the image as ILLUSTRATION goes, it is not irrelevant. Here the sea “stopped raging” when the crew of the boat old Jonah had booked passage on to Ninevah threw his butt overboard ‘cause they figured he was causing the storm. A “big fish” swallows him and three days later pukes his slimy, sorry self out onto dry land. Ok. Big fish, not a whale. However, if you consider that Melville refers to whales in Chapter 30 of Moby-Dick as “fish,” knowing full well that they were mammals (see the chapter about the whale’s penis called “The Shroud’) why would or should I assume that the writer of this 1500 year old story who was a long way away from whaling grounds would have known any better? So, I use a whale. It’s logical. It’s dynamic as form. And it just happens, as I configure it, to recall the cross. That is fitting in light of the Christian tradition of interpreting this very Jewish story as a metaphor for the death, entombment, and resurrection of Christ. I could go on, but you all don’t have the space.

|

And the Sea Stopped Raging |