distributed by

Sandy Tilcock lone goose press

541-465-9079

| |

| HOME |

| SEE INSIDE THE BOOKS |

| RODERICK HAIG-BROWN |

| THE BEAVERDAM PRESS |

| MAKING THE DIARIES |

| CONTACT / ORDER |

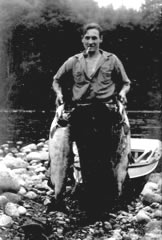

from photo album that accompanies

Excerpts from the

Diaries of Roderick Haig-Brown

About Roderick Haig-Brown

Roderick Haig-Brown (February 21, 1901 - October 19, 1976) published twenty-three books during his lifetime (six more were published posthumously), wrote numerous articles and essays, and created several series of talks and historical dramas for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. His sense of responsibility toward the environment can be seen in the list of organizations of which he was a member. He was a trustee of the Nature Conservancy of Canada, an advisor to the BC Wildlife Federation, a senior advisor to Trout Unlimited and the Federation of Flyfishers, and a member of Federal Fisheries Development Council and the International Pacific Salmon Commission. Haig-Brown was also named a Magistrate for the Province of B.C in 1942 and Chancellor of the University of Victoria from 1970 to 1973.

Honors and Awards

Roderick Haig-Brown was awarded the prestigious Harkin Conservation Award by CPAWS (Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society) in 1975. The award "honors individuals who have made a significant contribution to the conservation of Canada's parks and wilderness areas." In 1965, he was given the Vicky Metcalf Award by the Canadian Authors Association, an award which honors the writer for a body of work "inspirational to Canadian youth."

Roderick Haig-Brown Provincial Park, encompassing the entire length (11km) of the Adams River and site of the largest sockeye salmon run on the West Coast, was named in his honor. So was Mt Haig-Brown, a 6390' (1948m) peak in Strathcona Provincial Park on Vancouver Island.

Since 1991 the Federation of Fly Fishers has given an award in Haig-Brown's name, which "recognizes a fly fishing author whose work embodies the philosophy and spirit of Roderick Haig-Brown, particularly, a respect for the ethics and traditions of fly fishing and an understanding of rivers, the inhabitants and their environments." The Canadian Conservation Achievement Awards Program, sponsored by the Canadian Wildlife Federation, established the Roderick Haig-Brown Award in 1985 to "honor one of Canada's greatest outdoors person and writers on outdoor topics." BCWF (B.C. Wildlife Federation) also sponsors the Roderick Haig-Brown Memorial Conservation Award, dedicated in 1981, to "...perpetuate the memory of a long time resident of Campbell River, who was recognized as one of the world's renowned writers, lecturers, and conservationists." BC Book Prizes, which celebrates the achievements of BC writers and publishes, issues a yearly Roderick Haig-Brown Regional Prize.

Early Years

Haig-Brown was born and raised in England. When he was only ten years old, his father was killed heroically in the first World War. He and his mother and two sisters moved to his maternal grandfather's estate, where his training as a sportsman, started by his father, was continued by uncles and game keepers. From them he learned that fishing and hunting were as much about nurturing and care as they were about catching and killing.

After being expelled from his father's and grandfather's school for truancy, he continued his education with a tutor and glumly considered entering the civil service. Then, in 1927, the opportunity arose to travel to Washington State to work for a relative's lumber company. The move was the turning point in his life.

For three years he worked in logging camps in northern Washington, then on the Nimpkish River in northern Vancouver Island, British Columbia. He later described Vancouver Island in those days as "all river and forest and mountain on the grand scale, full of secret possibilities - hidden lakes and swamps, narrow valleys with steep-walled canyons, abundant wildlife except in the deep forest, immense salmon runs, trout in every lake and stream. But what was known about it all seemed little more than rumours and old wives tales."

As he had promised his mother, he returned to England in 1930, determined to become a professional writer. The few articles that he sold brought in a very meager income, but he did succeed in publishing his first book, Silver: The Life of an Atlantic Salmon. This was the first of several children's books he wrote with animal heroes.

Haig-Brown wrote: "I think I knew then that I was a Canadian, that I might go elsewhere but my heart would settle nowhere else. There was nothing I wanted to write of except Canada, the part of Canada I knew, and nothing that I wanted to know so much more of. I could not bear not to be a part of it."

Later Years

In 1931 he returned and settled on the banks of the Campbell River, where he spent the rest of his life. He married Ann Elmore of Seattle and they bought a home they named Above Tide, now called Haig-Brown Heritage House. Here they lived for over 40 years, raising three daughters and a son. Reflecting back on this period, his son, Alan Haig-Brown writes, "Fishing in our family was not so much an end in itself. It wasn't even the means to an end. It was the means to a presence - a presence in our environment, a place from which we could take some responsibility for that environment through a connection to it."

Haig-Brown wrote prolifically on a variety of topics, but it is his fishing books, among them Pool and Rapid (1932), A River Never Sleeps (1946) and four seasonal collections of essays beginning with A Fisherman's Spring, that ensured his reputation. George Woodcock said that "with the possible exception of Hugh MacLennan," Haig-Brown "was the best of all Canadian essayists." In his nonfiction, Haig-Brown was able to speak as a teacher, using facts and figures combined with his easy, conversational tone to teach the message of conservation. As critic Anthony Robertson observes, "It is a voice that resonates with decency, intelligence, integrity and presence. Its language is plain, its images clear and simple. It is a style lacking in special effect, able to reveal to a surprising degree the full dimension of the seen and felt."

A concern for conservation, long a part of his writing, took a more public and political turn as time went by. He spoke widely in Canada and in the United States for the budding conservation movement. In the 1950s he fought against ambitious hydroelectric projects planned by the British Columbia government that threatened salmon rivers. Haig-Brown said that conservation means "fair and honest dealing with the future, usually at some cost to the immediate present." In the 1950s, such a view was unpopular. In those boom times, an advocate of sober reflection who took the long view of man's impact on the natural world was seen as an enemy of progress. However, this 1950 statement, with few changes in language, could be written today: "It seems clear beyond the possibility of argument that any given generation of men can have only a lease, not ownership, of the earth; and one essential term of the lease is that the earth be handed on to the next generation with unimpaired potentialities. This is the conservationist's concern."

Bibliography:

Roderick Haig-Brown, by Dennis Smith, Creative Director, 7th Floor Media. The Heritage Post, Spring 1998

Learning River Currents with My Father, by Alan Haig-Brown. Wild Steelhead & Salmon, Spring 1997.